|

|

|

| Photo courtesy and copyrighted by the New Hampshire Historical Society |

This Concord Coach, circa 1852 appeared at the New York World's Fair

of 1939 and was later put on display at the Boston & Maine Railroad Station in Concord, New Hampshire. It is now in the

collection of the Museum of New Hampshire History at Eagle Square in Concord, N.H. Stop by and visit.

They carried precious stones from the diamond mines of

Kimberley and were so useful in opening the sheep ranges of Australia that in 1955 that country issued a special postage stamp

bearing the likeness of a Concord Coach and commemorating their part in her history. Three enterprising New Englanders established

a coach line in Chile, connecting Valparaiso and Santiago, and equipped it with sixteen vehicles from the Concord works.

They

lived a hard and adventurous life, these coaches, but they thrived on tough usage and did not wear out quickly. One of them

was returned to the works for a few slight repairs in May, 1885, after having been in constant use for thirty-five years.

No wonder a troubled commentator raised the question, "If they last that long, where is the demand for continued business

coming from?" Nobody answered him, and the coach rolled out on the road again, good for ten years more, at least.

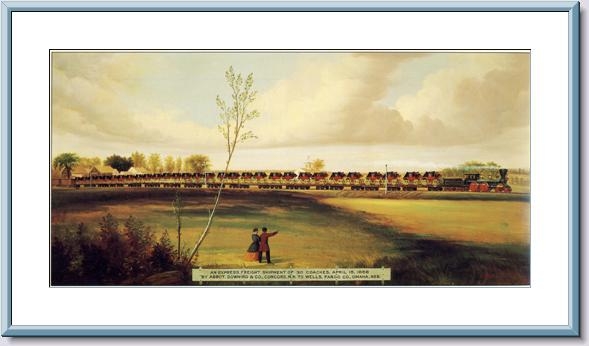

AN EXPRESS FREIGHT SHIPMENT OF 30 COACHES, APRIL 15, 1868 BY ABBOT-DOWNING & COMPANY, CONCORD, N.H. TO WELLS FARGO COMPANY,

OMAHA, NEBRASKA. Photo courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

Information on the artist John Burgum.

Boys were taken into the works as apprentices, their honesty and application vouched for by their fathers, and they were expected

to serve for six years in this capacity while learning the trade. But the company ledgers show that many of these "boys"

stayed on for forty or fifty years, and family names keep reappearing. Building coaches in Concord, a hundred years ago was

a good trade and a respected one, and there are indications that it not only provided a livelihood for many families but was

a source of pride and satisfaction to those who engaged in it. Not all of them could paint the doors with faultless landscapes,

as John Burgum could, or shape the handsome scrollwork with the delicate touch of Charles Knowlton, but they could all listen

eagerly when word came back to Concord of the part its coaches were playing in the world, listen and feel that they had a

share in it, too.

Concord Coaches carried the Overland Mail across the plains and the Rockies. Bandits and Indians rifled them, and desperadoes'

bullets dented their sleek basswood sides. They were loaded on flatcars and shipped west. They were stowed in the holds

of ships in Boston Harbor and carried on the long voyage around Cape Horn, to be used for transporting bullion in the California

goldfields. Wells Fargo ordered thirty heavy coaches at once, to be "elegant," with red bodies and yellow running

gear. It took a year to complete them, and they were shipped to Omaha on a special train of fifteen long platform cars.

Four box cars carried sixty-four sets of Hill harnesses, the whole shipment valued at $45,000.

|

|

Abbot-Downing Concord Coach

|

|

Employees outside the Abbot-Downing factory.

As the century grew older, Abbot-Downing devised a number of other vehicles, and their aristocratic and elegant coaches acquired

a score of humbler cousins, all of them just as useful and many as gaily painted. Consider, for instance, the pie wagon.

This was a sort of light express cart with oiled canvas duck sides and two narrow cases inside to carry the baker's wares,

but its framework was painted in vermilion and dark carmine trimmed with cream and light blue. The ambulance was painted

dark brown, with a white interior, and had two lanterns, a medicine chest, and a seat for a physician. There were two-wheeled

gigs designed for New York City fire chiefs to dash about in, fire wagons, patrol wagons, Boston Caravans, drays, tally-ho

coaches, beer wagons, street sweepers, and all kinds of special creations.

It was not the spreading out, or diversification, that brought about the final end of this famous New Hampshire industry;

rather it was that men die and times change. After the death of the partners, the Abbot-Downing assets were transferred to

Josiah Fernald, and he in turn passed them on to the Wells Fargo Company, which was interested in acquiring them for sentimental

reasons to perpetuate the name historically. Gasoline and steam-driven engines had come to take the place of the high-stepping

roans and bays, and if any coaches go rumbling down our superhighways they must be of the ghostly variety, seen only after

dark on Halloween.

Abbot-Downing Company - circa. 1893

|

|

| Photo courtesy of NH Historical Society |

Special thanks to SHIRLEY BARKER for this wonderful article.

|